Life of Common Sailors Who Served in the Azov Fleet

Life of Common Sailors Who Served in the Azov Fleet

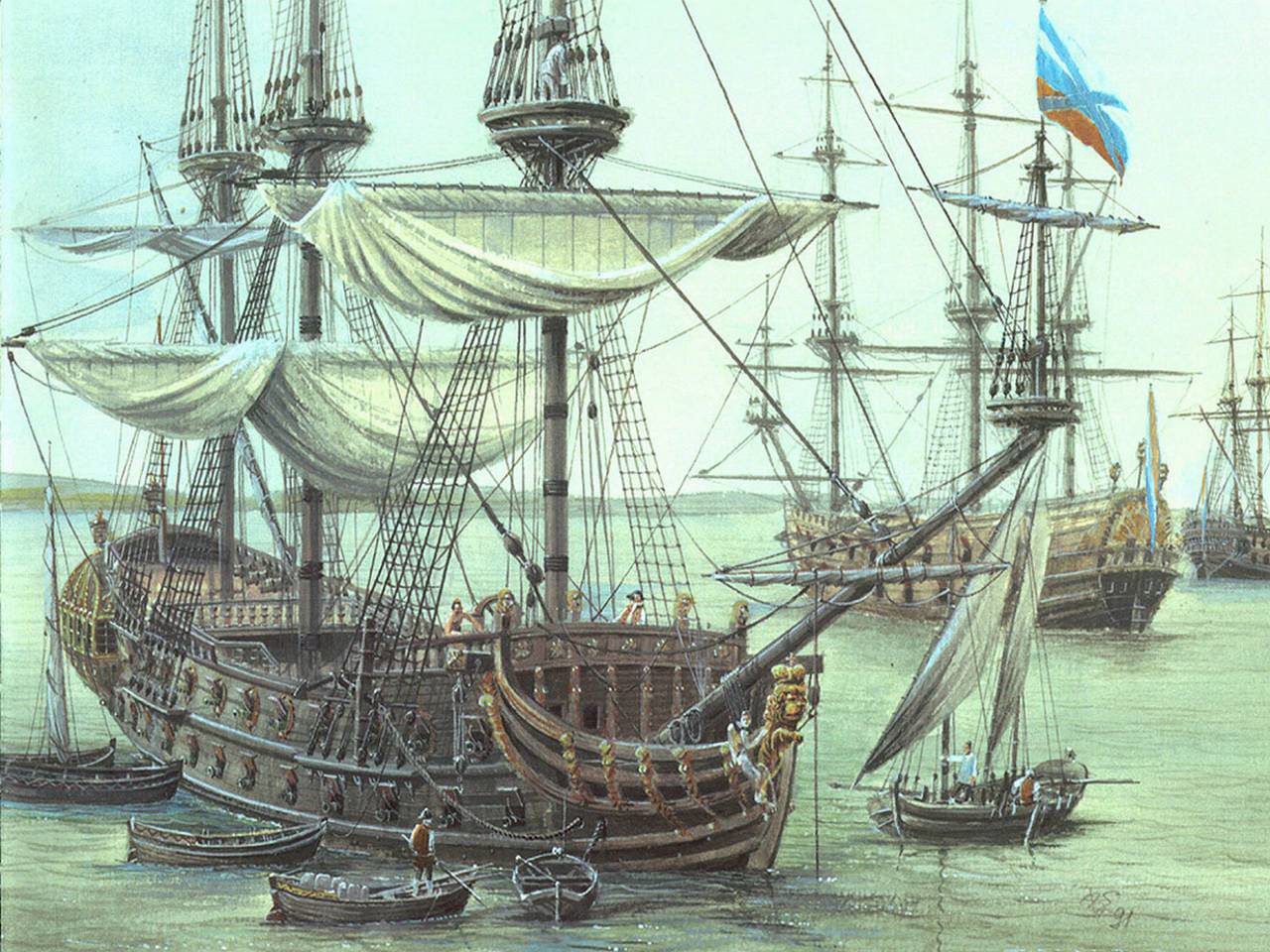

The service on board the sailing ship in the 18th century is usually associated by contemporaries with the romanticism of sea adventures, captivating voyages of pioneers and glorious victories in sea battles. All that is true, however, «the reverse of the medal» was the life of common sailors, with its dangers, privations and hard physical work in extreme conditions.

The daily routine of sailors in the days of Peter the Great was described best in the Navy Regulations, dated April 13, 1720, that were based on the previous rules, with the 15 year-long experience of service at the Azov and Black seas taken into consideration. This document enables us to get an idea of the living conditions on naval vessels at Peter’s time.

The 18th century sailing vessels had very close quarters, as the ship-building technology of the time did not permit more space to be provided for the ship crew. For example, there were 253 men serving on the «Goto Predestinatsia»: such a number was required to do all sorts of work aboard the ship. Besides, sailors would be recruited with a minor reserve created, as the death rate due to diseases (dysentery, catarrhus and sea scurvy) would at times surpass the combat losses, the fact that had to be taken into account during preparation of the ship for a campaign.

However, it would be unfair to state that in those times there was no medical aid at all. Large Azov Fleet ships necessarily had a doctor on board. As a rule, ship’s doctors were foreigners. In March, 1697 Peter the Great instructed his ambassadors to hire one European doctor supplied with medical appliances and pills for each particular ship built in Russia. Nevertheless, the level of the 18th century medicine did not permit doctors to radically change the situation and so the death rate in the Navy remained rather high.

The 24-hour periods were divided into six 4 hour-long watches. During each relief one third of the ship crew kept watch, other one third did the current work needed, and the rest were asleep.

The sailors were mainly accommodated on the gun deck — amidst the cannons, in rat-overrun quarters, close and damp. The vicinity of cannons not only caused inconvenience, but it threatened the sailors' lives. At times in case of heavy pitching and rolling the lines holding the cannons to the ship board would break, one-and-a-half-ton cannons would roll on deck, crushing the clumsy and sleeping sailors.

Most of the time sailors would spend in dim compartments: to avoid fire hazard the regulation of lighting on ships was exceptionally strict. Lanterns would be on only in the captain’s cabin and in the cook-room on the bow, where cooking would be done.

Naval officers and men were entitled to good food. On each warship provision was made for a galley (cook-house), wherein a ship stove was installed to cook hot meals. As to the energy value, the Russian sailor’s food ration of 3900–4300 kilocalories practically corresponded to the present-day food standards for 20–40 years-old men doing physical work.

In one of his letters written in 1706 Peter the First specified the list of food products needed to provide an adequate ration. Included in that ration were ship biscuits, meat (mainly salt junk, however, taken along for campaign were also small stock and poultry in order to have fresh meat), ham, butter, fish (cod was especially in great demand), cereals and salt. The deficiency of vitamins was «compensated for» by drinking beer. According to the Regulations of 1720 seven buckets of that drink were due to each sailor for 28 days, i.e. 3 liters a day per man. However, that beer was not very strong, it was more like kvas. To maintain their fighting spirit the sailors were issued a glass of vodka (123 ml) four times a week.

The sailors were never underfed, but the quality of food left much to be desired: in damp ship spaces the food products would be spoiled, rat-bitten and infested with insects and worms. The storage of drinking water was also a problem. When barreled, it would soon turn greenish, smell stale and resemble swamp water.

The hardships and trials required the sailors' stamina and moral courage. Under severe conditions the men were supported by the church — there was a chaplain on each ship, religious books and a portable altar were available. In the course of the campaign there were morning end evening services every day. These were attended by all crew members who were not on watch.

It stands to reason that the sailors' daily routine described here does not reflect in full the living conditions on the ships of the time past and gone. Nevertheless, it remains clear, that the life and service on naval vessels in the early 18th century was far from easy. Staying in close, damp quarters, in unsanitary conditions, the sailors were required to do hard physical work, to be skillful and adroit, when defending their wooden vessel not only in battles, but also, when confronted with raging seas. This ordeal went on for as long as the men could stand it. In 1705 Peter the First introduced a system of recruitment under which the service in the army and navy could last «till one was fit and strong enough for it." Therefore, commemorating the victories of the Azov and other Russian Fleets, we ought to keep in memory the difficult life of common sailors and to pay tribute to them.